As the Supreme Court of the United States returned from its summer recess on Monday, Oct. 1, one of the first issues heard during its new term involved a timber giant with a major presence in Columbia County, a rare frog, and a challenge of the U.S. Endangered Species Act of 1973.

In the case, which has been appealed all the way to the high court since 2012, the Weyerhaeuser Company – owner and operator of a veneer plant in Emerson and a nursery in Magnolia – and a Louisiana landowner are at odds with the federal government over 1,544 acres in St. Tammany Parish involuntarily deemed a “critical habitat” for the endangered dusky gopher frog. The problem, though, according to the petitioner, is that the frog has not called the acreage home since 1965, and the land as it exists now cannot support the animal.

The seven-year-old case has been defeated in every lower court and ruled in favor of U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. The most recent ruling came in 2016 from the U.S. 5th Circuit Court of Appeals.

The matter began in 2011 when, according to a Sept. 13 New Orleans Times-Picayune report, the federal fish and wildlife agency classified thousands of privately-owned acreage in Louisiana as a possible breeding ground for the amphibian. The dusky gopher frog, also called the Mississippi gopher frog, is currently only seen in the Magnolia State, where approximately 100-150 still live in the wild just north of Gulfport, Mississippi.

The Louisiana land, owned by New Orleans resident Edward Poitevent and his family, is, according to the wildlife agency, the only area in the country that the frog could potentially rebreed if its natural homelands in Mississippi suffered a major drought and displaced the animal. But the acreage now, according to an Oct. 1 report by the Property and Environment Research Center, is full of lush commercial-grade timber and not suitable for the frog.

To convert the land into a proper habitat, an abundance of the existing pines would need to be chopped down, new variations of foliage planted, and further accommodations made, including regular controlled property burns and clearing of the land. The Endangered Species Act also places certain restrictions on the area that would likley severely hinder most future development plans or industrial timber farming.

Poitevent claimed the endangered species “habitat” tag placed on his acreage – due in no small part to an tract that includes five ephemeral (seasonal) ponds suitable for the frog’s breeding – would devalue the parcels to the tune of $34 millions of dollars. It would also cost him personal expenses to convert the property for the frog even as it has not called the area home for over 50 years.

Weyerhaeuser Company, which filed the 2012 suit against the federal wildlife agency, has interest in the matter since it currently holds a 140-acre timber lease on the Poitevent family land that does not expire until 2043.

Oral arguments in the Supreme Court case began the morning of Oct. 1 in Washington D.C. in front of the eight-judge panel. Newly appointed Associate Justice Brett Kavanaugh was not yet sworn in to hear the matter.

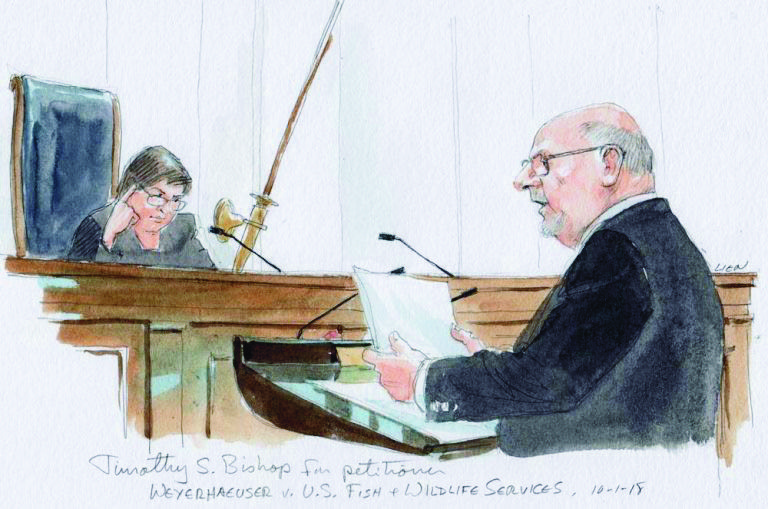

The session began with an opening argument by Weyerhaeuser attorney Timothy Bishop, where he challenged the Endangered Species Act’s powers. He cited a 1978 Congressional amendment to the law that, he said, narrowed the concept and expanse of what was deemed as a “critical habitat” for a nearly extinct species. He also claimed the government could not designate a habitat to include the entire area which a rare animal, in theory, survive.

Almost immediately, Bishop was peppered with a “hypothetical” by Associate Justice Elena Kagan that seemed to challenge the petitioner’s position.

“So habitat A where the species is, is no longer any good,” she said. “Habitat B, it can’t — it won’t conserve the species if left just as it is, but it only takes reasonable effort to conserve the species. Can the government designate that area as unoccupied, critical habitat?”

To her question, Bishop quickly answered “No.”

The Chicago-based lawyer stated that the land in question would take far more than the “reasonable effort” listed in federal law for the acreage to be converted into a suitable breeding and living area for the frog.

“I don’t rule out that the government might be able to justify a critical habitat designation when there are deminimis changes,” he said. “Where you’re really only talking about digging a few holes, where there is a very minimal change required in the land. That isn’t this case.”

The crux of Kagan’s questioning seemed to hinge on the word “habitat” and how it used in the law. She claimed that the term was not merely meant to mean “just where a species can live,” but goes far beyond that.

“There are also habitats that are outside the geographical area occupied by the species,” she said.

The left-leaning justices seemed to take the same approach as Kagan, with Associate Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg citing the similar Migratory Bird Act. Bishop argued that law did not apply since birds are seasonal occupants of an area.

She also asked what the major concern was for the landowner with the frog potentially living on the acreage.

“You are not commanded and you do not have to do anything to maintain the species,” she said, “It is to be used for timber farming.”

Bishop quickly disagreed with her viewpoint. He said the immediate effect of the critical habitat land classification forced upon his client by the government equated to a devaluation of the acreage by tens of millions of dollars.

“That is what it says in the agency’s economic analysis,” he said, “that there is an immediate loss in value.”

The reasoning for the value loss, Bishop claimed, is due to the substantial decrease of future business interests at the privately-owned land because of the federal development and cutting restrictions. To comply with the plan, not only would it mean a devaluation of the land, but also any past development efforts were all for naught.

“We have ourselves spent hundreds of thousands of dollars completely planning out and obtaining a rezoning of this land for development,” he said. “Those are wasted expenditures at this point. That was done before the critical habitat designation.”

Associate Justice Stephen Breyer asked if the case before him and his colleagues was a matter of an agency overstepping its bounds or if the area actually does fall within the range of the Endangered Species Act and could be easily converted into a proper habitat for the frog.

“The administrative record here shows that this land would have to be totally remade,” Bishop said. “…And that burden is not something that is allowed by language, plain language, in the statute.”

The second half of the hour-long oral arguments were pointed toward the respondent, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and its representative, Deputy Solicitor General Edwin S. Kneedler.

Associate Justice Neil Gorsuch, known as being one of the more conservative members of the court, challenged the same “habitat” question raised by Kagan, only from the opposite end of the spectrum. He asked what was the true limit to the word and cited his own hypothetical that included the abilities of modern greenhouse technology.

“What’s the limit?” he asked. “I mean, you could require this piece of property be in Canada. It could accommodate the species so long as you invested $100 million to put in ephemeral ponds, change the loblolly pines to longleaf and do all this.”

Kneedler answered back, “Well, it has to be, according to the Service here, reasonable efforts.”

Associate Justice Samuel Alito also piggybacked on the Gorsuch line of questioning.

“What’s the definition of reasonable,” he asked.

Without giving many specifics, the federal attorney kept citing language in the law that, he said, designated the land for the government tag. He stated that since the land was not already commercially developed, it was perfect for the “critical habitat” tag.

“I think there’s a big distinction between whether, in this case, the upland habitat has been transformed to such an extent that it’s destroyed, like if there was a shopping center there or a housing development there, as compared to the upland habitat here,” Kneedler said.

But Gosuch continued with his questions.

“But why?” he asked. “And where does all this come from in the statute?”

Kneedler quipped back, “It’s throughout.”

The Justice also made it a point to state how the case before the court will be “spun.” He said it is not a matter of the frog’s existence, but rather one strictly dealing with the law and the federal government’s limitation of power.

“We’ve already heard questions along this line, as a choice between whether the dusky gopher frog is going to become extinct or not,” he said. “That’s not the choice at all. The question is, who is going to have to pay and who should pay for the preservation of this public good?”

Gorsuch stated it would be hard for the public to feel compassion for a giant corporation such as Weyerhaeuser, but to just imagine if the matter at hand involved a small family farm and the government demanding it to make such major alterations, all in the name of what was “reasonable.”

“Is there some formula,” he asked, “some percentage of the value of the family farm that would have to be required for this reasonable restoration before that becomes unreasonable? Can you provide any guidance on that?”

Kneedler answered, “I don’t think there would be a hard-and-fast rule.”

As was per usual, every justice in the session interacted in the arguments except Associate Justice Clarence Thomas. He asked no questions and had no rebuttals, according to SCOTUS audio and transcripts.

To close the oral arguments, Bishop stated his viewpoint once more. He said that the federal wildlife agency has overstepped its bounds in the case and that the frog can survive by other methods if a natural act displaces it from its Mississippi home.

“Not one person has talked, from the government, or from any of the nature conservancy or other groups that buy easements on property have talked to any of the owners here,” he said.

He also cited the permitting process with the federal government that would need to take place, should his side fall on the wrong end of the court’s ruling.

“If we need to apply for permits, we get to use 40 percent of the land for development and we have to turn 60 percent of it over for frog habitat,” Bishop said. “We don’t think that that is an appropriate use of our land, given that this is not habitat to begin with.”

With the oral argument portion of Weyerhaeuser Co. v. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service now over, the court will reach its decision then opinions will be released. They are typically issued at the end of a term.

With the SCOTUS term beginning the first Monday of October and ending in late June or early July, the decisions are usually released by mid-summer of the following year.